Dilbeck’s Legacy Grows as Tulsa Embraces Its Architectural Treasure

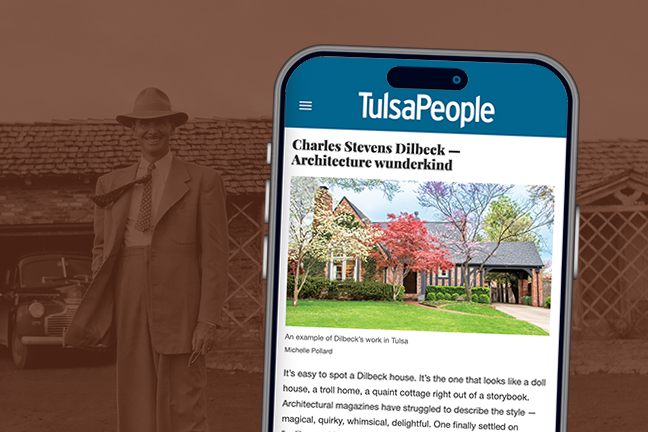

We at the Dilbeck Conservancy are grateful to Tulsa People and to writer Connie Cronley for the engaging profile of Charles Dilbeck in the magazine’s Home-Spring 2025 edition. The article, “Charles Stevens Dilbeck — Architecture Wunderkind,” celebrates Dilbeck’s impact on Tulsa’s built environment, from his early work in Tulsa’s Florence Park and University of Tulsa neighborhoods, to grand homes in Maple Ridge, Bren Rose, Swan Lake and the Utica Square area. We are honored to be mentioned for our part in this effort, through dilbeckconservancy.org and ongoing outreach.

As Cronley puts it, “It’s easy to spot a Dilbeck house. It’s the one that looks like a doll house, a troll home, a quaint cottage right out of a storybook. Architectural magazines have struggled to describe the style — magical, quirky, whimsical, delightful. One finally settled on ‘unlike anything else in town.’”

“Whether cottage size or baronial mansions,” she writes, “Dilbeck’s distinctive details include massive chimneys, tall windows, unusual stone and brick patterns, vaulted ceilings and often a small turret at the front entrance. Sometimes he used salvaged items such as an old brick sidewalk for a fireplace.”

It was a style entirely his own—charming, unexpected, and defiantly individual.

“His Hansel-and-Gretel-style cottages were a romantic version of French and Irish farmhouses, although he had not traveled to Europe to see them. He invented the style based on popular magazines of the day. ‘Contemporary houses leave me cold,’ Dilbeck said. ‘Roofs go straight up and then just stop. They remind me of a dog with his leg in the air.’”

Cronley recounts how Dilbeck moved to Tulsa with his family when he was 8. He learned the building trades firsthand at his father’s lumberyard, and his talent quickly showed: he sketched a church at 11, and by 16, he was second-in-command of an architectural department. After two years studying architecture at Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State University), he left to launch his own firm. Just 18, he was tapped by the celebrated architect John Duncan Forsyth to help on the grand Marland Mansion project in Ponca City.

The article highlight’s Dilbeck’s remarkable output. By the time he was 24, he had completed roughly 240 Tulsa residences. He then headed south to Dallas, where he turned out hundreds of homes that bore his unmistakable flair. He later pivoted to expansive ranch houses inspired by childhood trips through the Oklahoma Panhandle and West Texas.

Dilbeck also kept pace with America’s growing love affair with the automobile, pioneering the “motor hotel” concept—roadside travel courts that evolved into modern motels, Cronley writes. His portfolio ballooned to include eateries and prominent hotels across Texas, Florida, New Mexico, and California. His vision even captured the imagination of Henry Ford, who enlisted Dilbeck in a forward-looking housing experiment that never materialized because of World War II.

Read the entire article here.